Architectural Furniture II | Joselo Maderista

From February 1 to July 6, 2025

Design, Fashion and Architecture Program

Coordinator: Rodrigo Santoscoy

BARBAPIÑA Arquitectos, Tatiana Bilbao Estudio, Jose Dávila, Saúl Figueroa y Ana Victoria Pérez Gil, Alonso Mendoza and Jorge A. Romero, Juan Palomar, Jesús and Luis Vasallo, Daniel Villanueva Sandoval

Lola Álvarez Bravo Gallery

In the early 1940s, the Japanese-American designer George Nakashima traded architecture, a profession in which he’d already found considerable success, for furniture design—“a new vocation,” he wrote in his 1981 memoir The Soul of a Tree, “that I could coordinate from beginning to end.” Famously unyielding in his studio, Nakashima earned global fame for tables and chairs whose organic forms deferred to the natural grain of wood. Trees, “more God-like than man,” as Nakashima said, were his only collaborator.

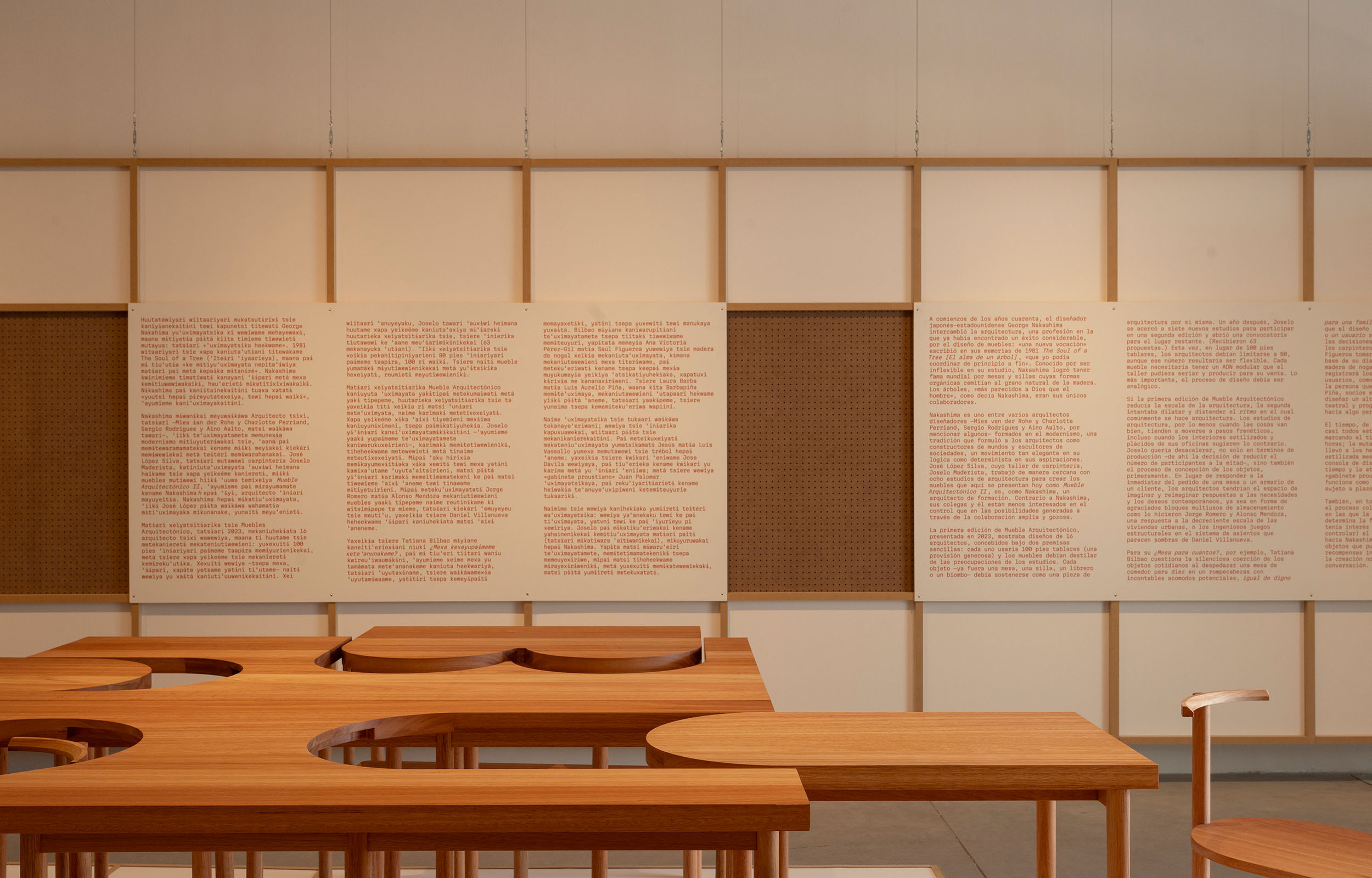

Nakashima was one among many architect-designers—Mies van der Rohe and Charlotte Perriand, Sergio Rodrigues and Aino Aalto, to name just a few—trained in modernism, a tradition that framed architects as builders of worlds and sculptors of societies, a movement as elegant in its logic as it was deterministic in its aims. José López Silva, whose carpentry workshop, Joselo Maderista, worked in close conjunction with eight architectural studios to create the furnishings presented here today as Mueble Arquitectónico II, is, like Nakashima, an architect by training. Unlike Nakashima, he and his colleagues are less interested in control than in the possibilities generated through joyful, wide-ranging collaboration.

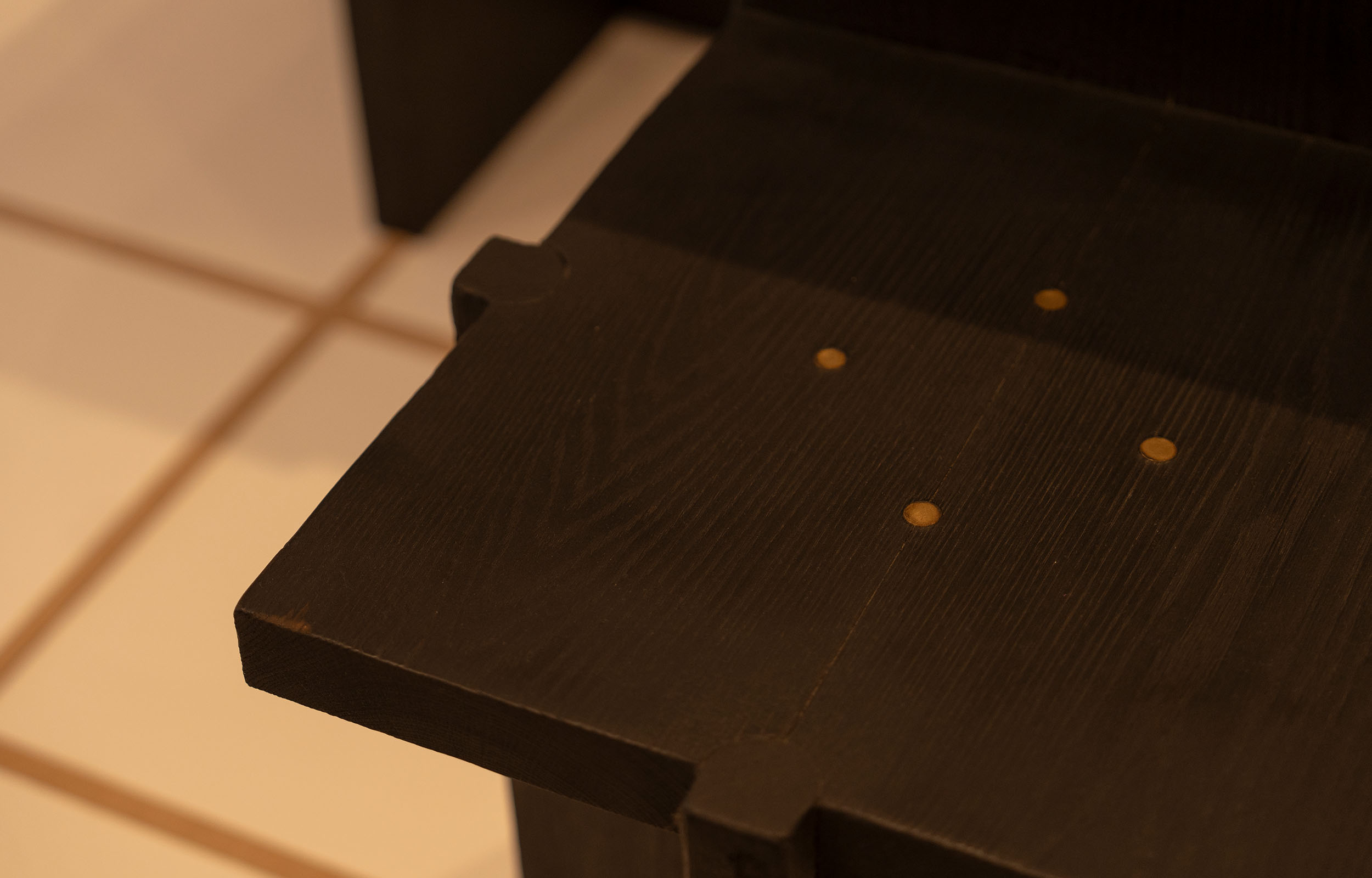

The first edition of Mueble Arquitectónico, presented in 2023, featured designs by 16 architects conceived under two simple guidelines: each could use 100 board feet (a generous allowance) and the furniture should distill their office’s preoccupations. Every object—be it a table, a chair, a bookshelf or a biombo—would stand as a piece of architecture in itself. A year later, Joselo approached seven new offices to participate in a second edition and opened a competition for the remaining spot. (They received 63 entries.) This time, rather than 100 board feet, the architects would limit themselves to 80, though the number would turn out to be flexible. Each furnishing would need to have a modular DNA that the workshop could serialize and produce for sale. Most importantly, the design process should be analogue.

If the first edition of Mueble Arquitectónico reduced the scale of architecture, the second aimed to dilate and distend the rhythm at which architecture is often made. Architecture studios, at least when things are going well, tend to move at a frenetic pace, even if the sleek, placid interiors of their offices suggest otherwise. Joselo wanted to slow down, not just in terms of production—hence the decision to reduce the number of participants by half—but also the process of conceiving the objects in the first place. Instead of responding to a client’s immediate demand for a table or cabinet, the architects would have space to imagine and reimagine responses to contemporary needs and desires, whether in the form of Jorge Romero and Alonso Mendoza’s graceful multiuse storage blocks, a response to the shrinking scale of urban homes, to the clever structural games in Daniel Villanueva’s shadow-like seating system.

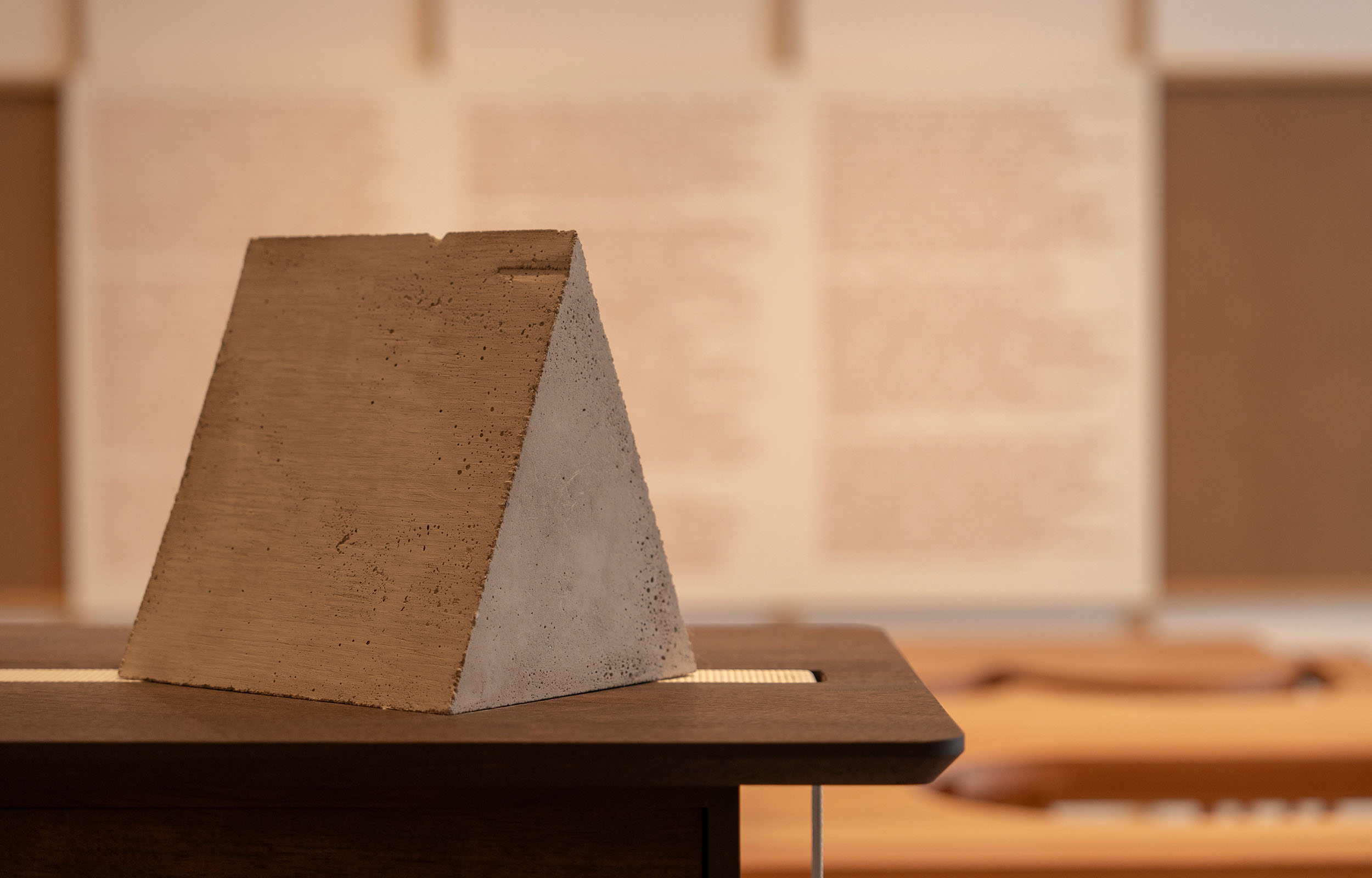

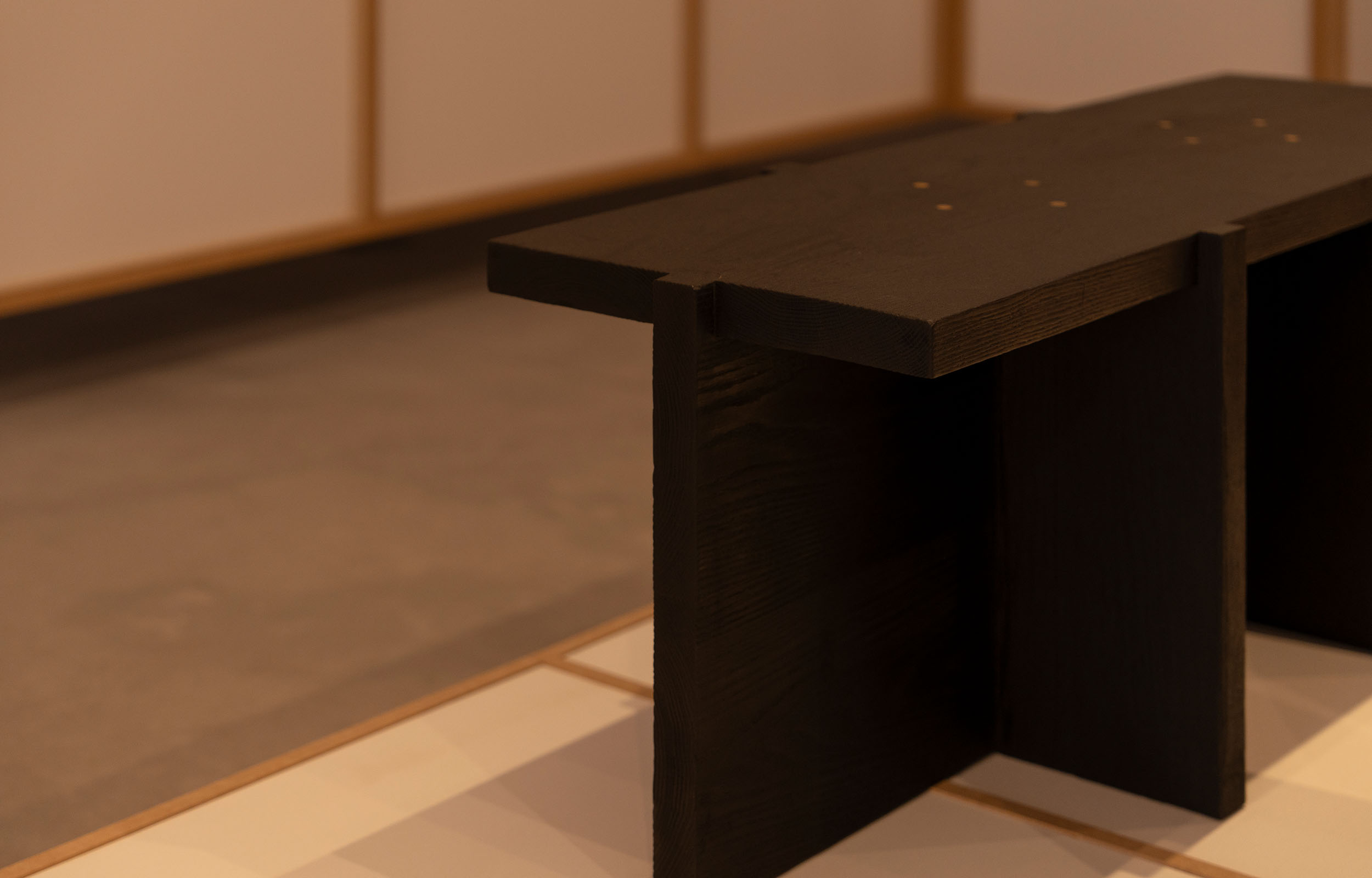

For her Mesa para Cuantos?, for instance, Tatiana Bilbao questioned the quiet coercion of everyday objects by shattering a dining table with room for ten into a jigsaw puzzle with countless potential arrangements, igual de digno para una familia extendida—the normalized body that domestic design is usually meant to clothe—o un usuario solitario. Where Bilbao left the decisions of materials and finishes up to the woodworkers, Ana Victoria Pérez-Gil and Saúl Figueroa took materiality itself as the basis for their design, crafting a reading table in untreated nogal that, through time, will register the bodies and postures of its users much as shoes record the stride of the person who wears them. Laura Barba and Luis Aurelio Piña, partners in the firm Barbapiña, chose to design an altar that could transmogrify the theatrical, programmatic ritual of a sacred typology into something personal, fluid and secular.

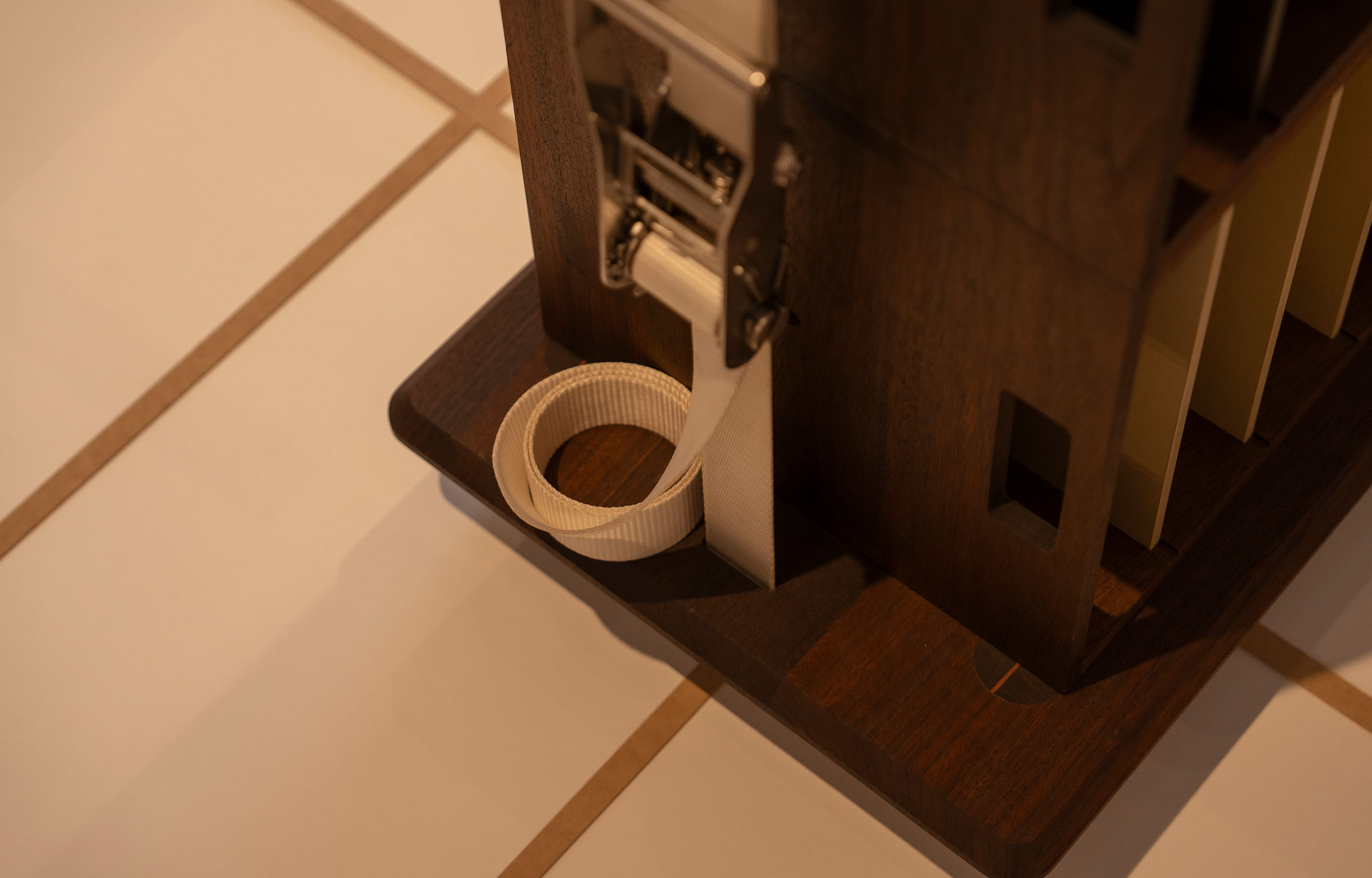

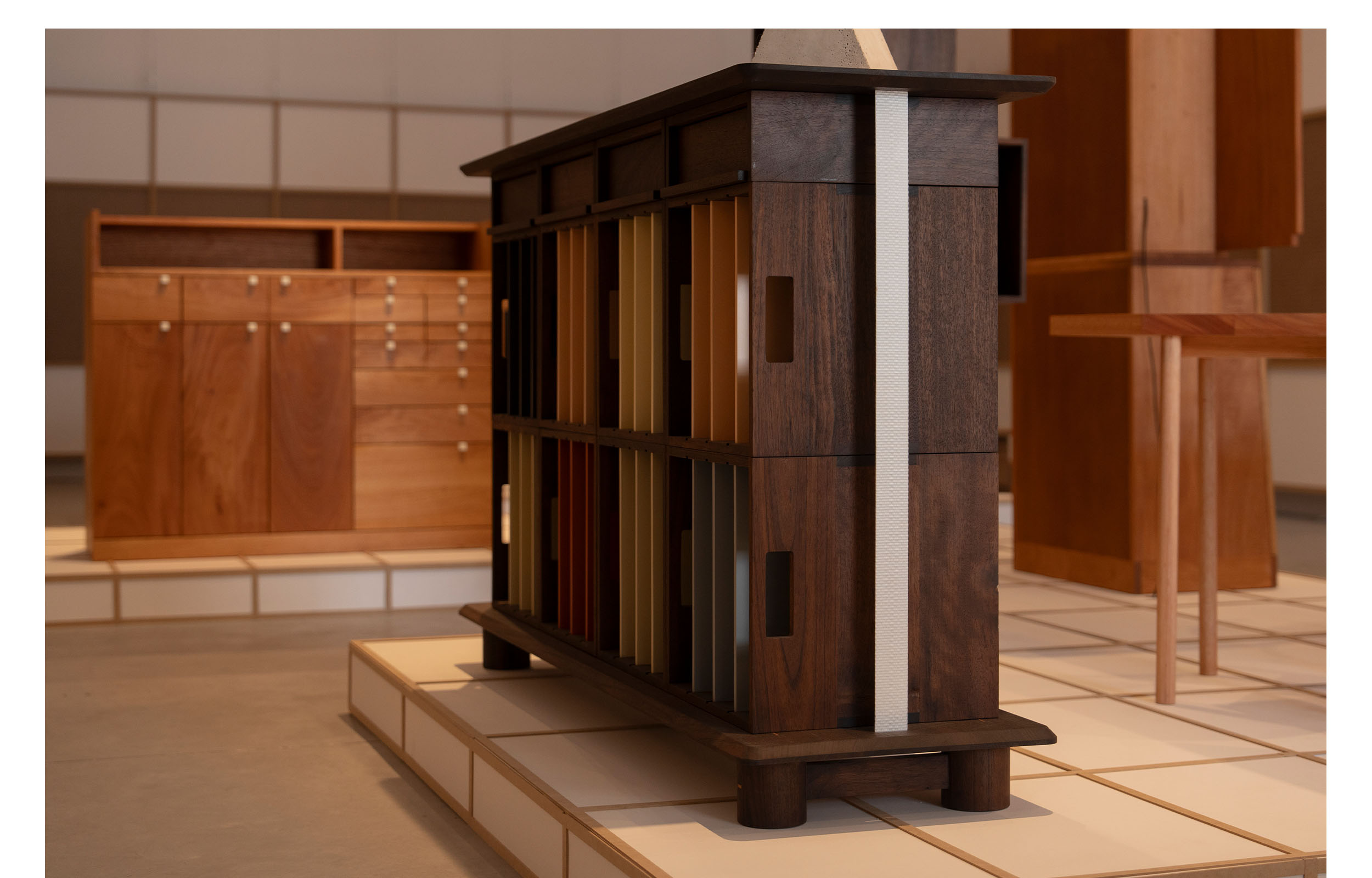

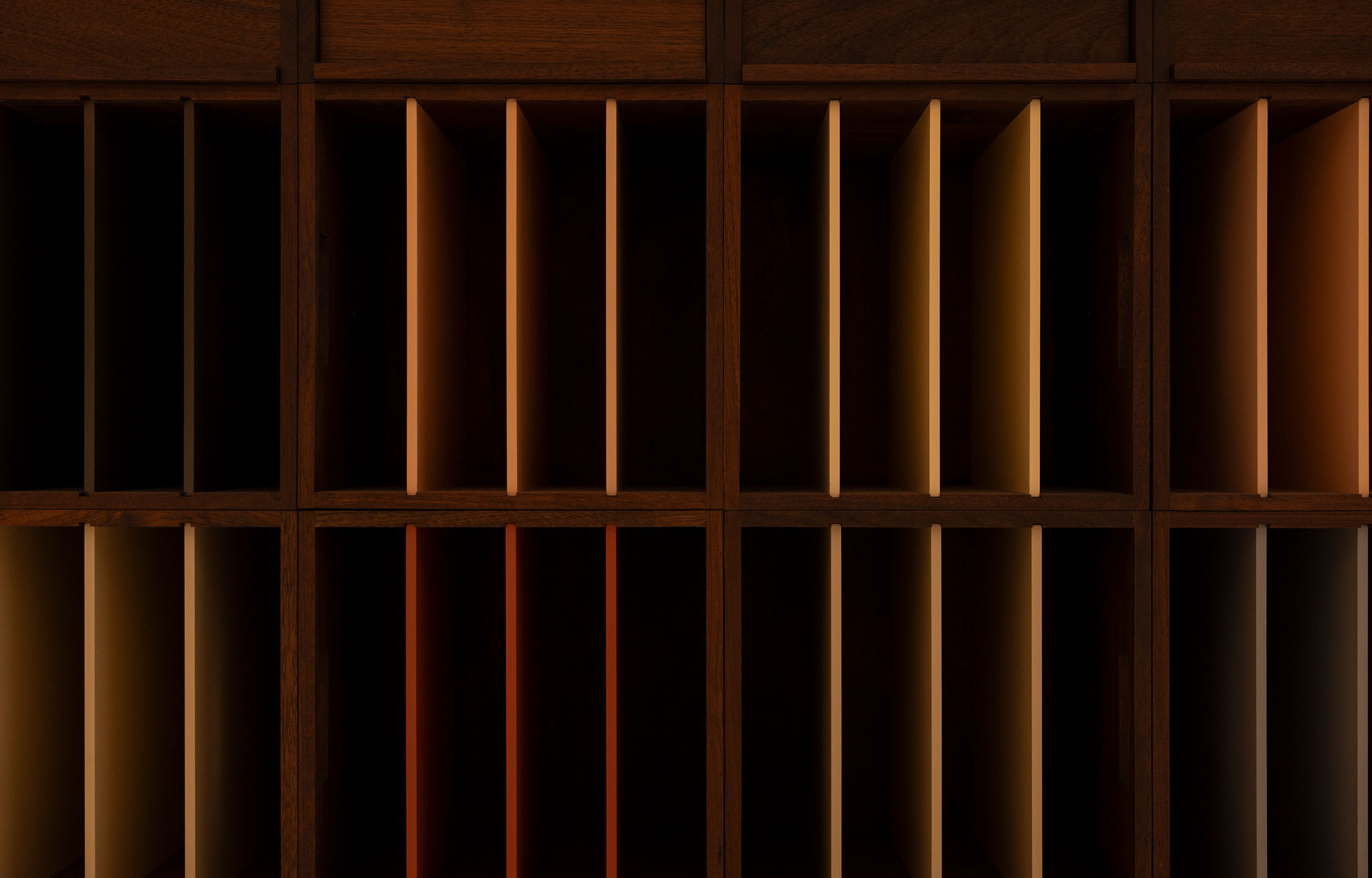

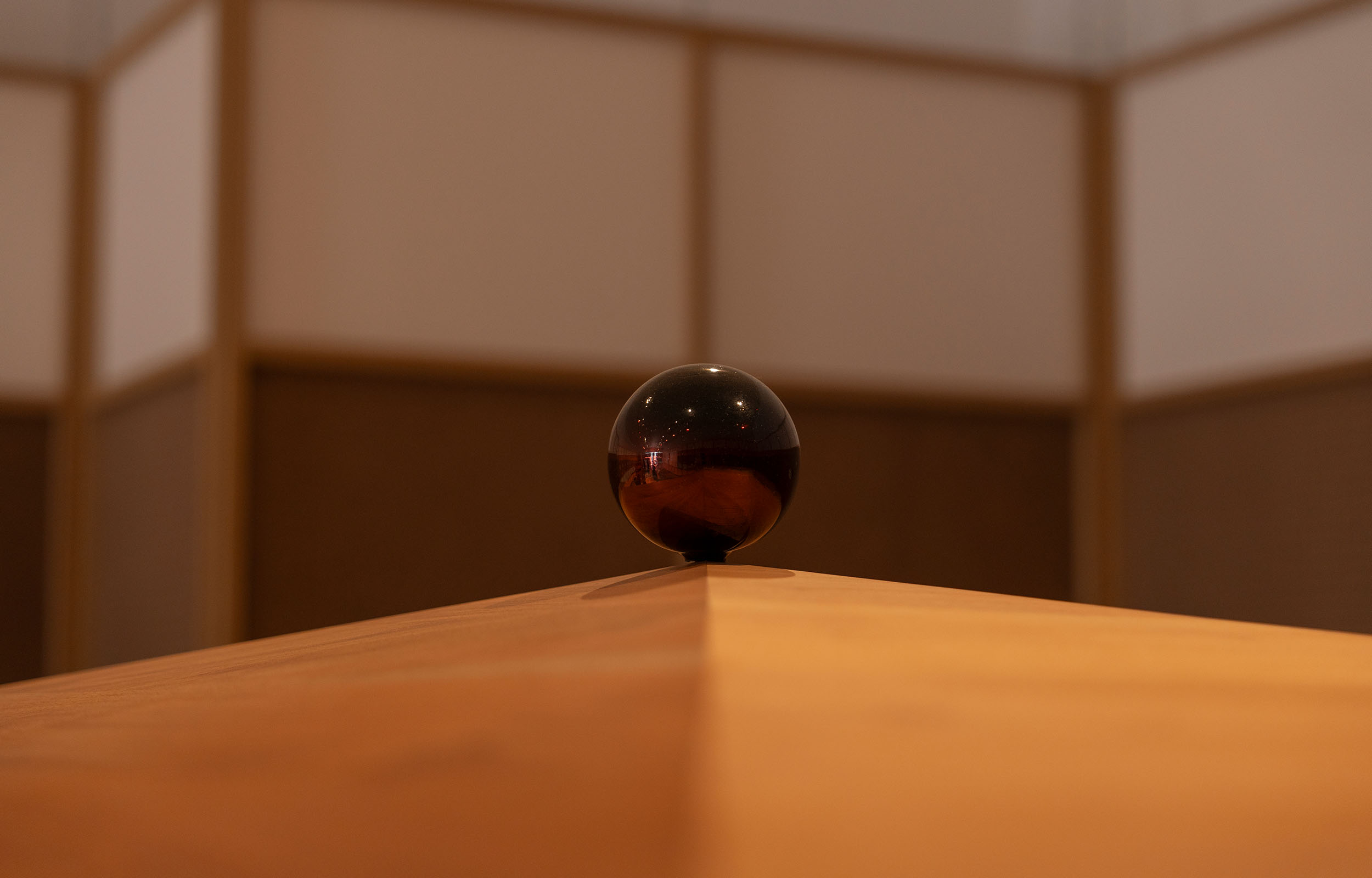

Time, in one way or another, manifests in almost all of these projects: the object as a clock, keeping time over years rather than hours; the mutation of painterly forms that brought the brothers Jesús and Luis Vassallo to their modish cloverleaf coffee table; Jose Dávila’s console for records, which reinsert time and attention into the act of listening; or Juan Palomar’s ‘Proustian Cabinet,’ which acts as an escape hatch from the time-bound world.

They also, in every case, express and distill the collaborative process itself, the ways in which form makes demands on craft and that craft determines form. Joselo, ultimately, had no interest in coordinating (that is, controlling) the process from beginning to end, as Nakashima did. Instead he made space for objects that could embrace the risks and rewards inherent in treating creation not as a soliloquy but as a conversation.

Info

Date:

20 December, 2024

Category: