The Underdogs | Mark Bradford

From February 4 to August 6, 2023

Curator: Viviana Kuri Haddad

Sala Luis Barragán

“Anger has its place. Anger has fire, and fire moves things… but I sing from intelligence”.

– Nina Simone

Having a conversation with Mark Bradford is a constructive and pleasurable experience, owing not only to the careful attention he pays his interlocutor, but also to the cascade of keen reflections he offers. Reflections made with grace and wit, because Mark is someone who is comfortable in his own skin and who fills the space around him with expansive generosity.

Regarding his own early years and his practice as an artist, I have heard him say that he always knew very well where he was coming from but was only interested in where he was going. The same is true (he has said) of the materials he uses in his work: regardless of where they come from, or however modest their origins ―found in the street, taken from merchant posters―, what really counts is when they take flight, when they become something else and speak of other things, taking part in a conversation about art and painting, transformed into something they were never intended to be.

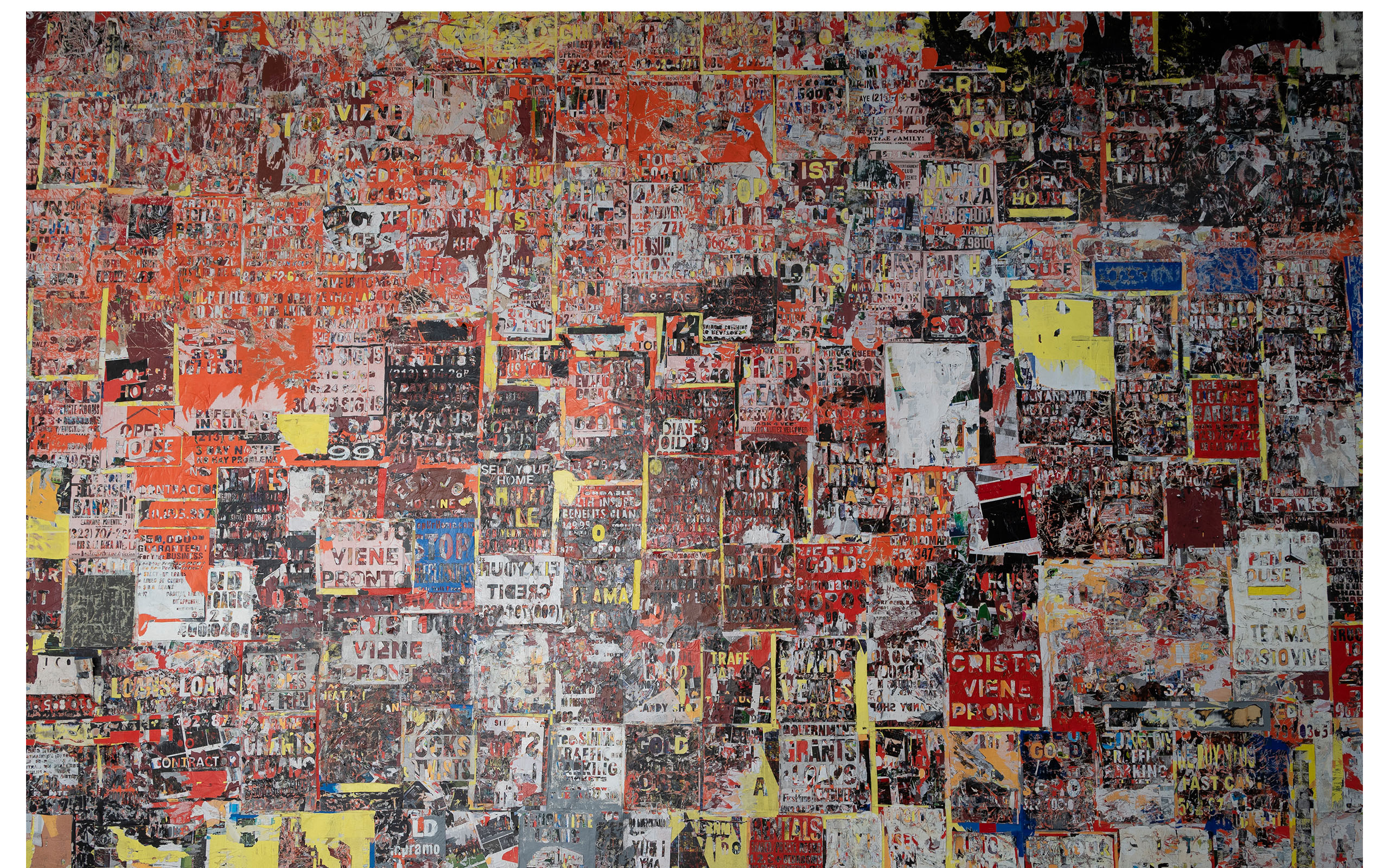

The superposition of layers of paper is characteristic of his work. Bradford integrates printed advertisements that he insists on transforming into something different: he folds and manipulates this refractory material and demands that it transform itself into exactly what he wants. It is clear that the choice of material, the different layers, and the contents of the posters carry a political charge, often mentioned in references to his work. This time, however, what Bradford does is to enter into the tradition of Mexican muralism, taking José Clemente Orozco as a reference: a painter with whom he shares a certain ideological affinity and ―I would add― a similar style. The blunt forcefulness and formal impact of both artists’ works, their quality, scale, and visual power, lend them a discursive autonomy that renders them timeless and valid on their own terms. At the same time, both artists feel a close identification with the tradition of popular prints. In Orozco’s case, the daily sight of José Guadalupe Posada, doing piecework printing jobs in the workshop of Vanegas Arroyo, would forever mark him as an artist. As for Bradford, in his early years he put up posters or intervened in those of others in his own Los Angeles neighborhood and all around the city.

The title of Mark Bradford’s exhibition The Underdogs is taken from that of the 1916 novel by Mexican writer Mariano Azuela, first published in English in 1929, with illustrations by José Clemente Orozco, who had been living in New York City since 1927. Bradford’s mural Man of Fire (2023) consists of layers of commercial posters intercalated with sheets of paper whose colors correspond, one after another, with those used by Orozco in his own mural of the same name, executed in the Hospicio Cabañas in Guadalajara.

Fire: a common denominator, a transformative force. The anger possessed by fire channeled as an agent of change. Urban artists both, they were influenced early on by the medium of paper, by cheap prints for popular consumption, which gave expression to a critical spirit and denunciations of inequity. In the case of Mark Bradford, the signaling, the viewpoints or disagreements are always made through horizontal dialogue in the same arena. Opposing viewpoints, but unafraid to show themselves, expressed without any sense of being marginal, and without resentment or grudges.

Some thirty young people participated in the on-site creation of the mural, some of them art students or up-and-coming artists, from many different backgrounds. During Mark’s residency, his conversation and personal interactions were no less important than his artistic practice. When Mark Bradford shares his own experiences, his conviction of the possibility of change, it is rather like the multiplication of the loaves and fishes.

The second piece in the exhibition is Float (2019), a cascade of strips of paper, salvaged and reconfigured, that the artist has yanked out of “pull paintings.” These enormous strips have been removed to form a new piece that expands their pictorial possibilities, where the space itself serves as a frame for three-dimensional painting. At the same time, the allusion to water can be read as the choice of a moving element, a cascade that leaps over one border only to continue along a new course of the river. The deafening crash of an end and a new beginning.

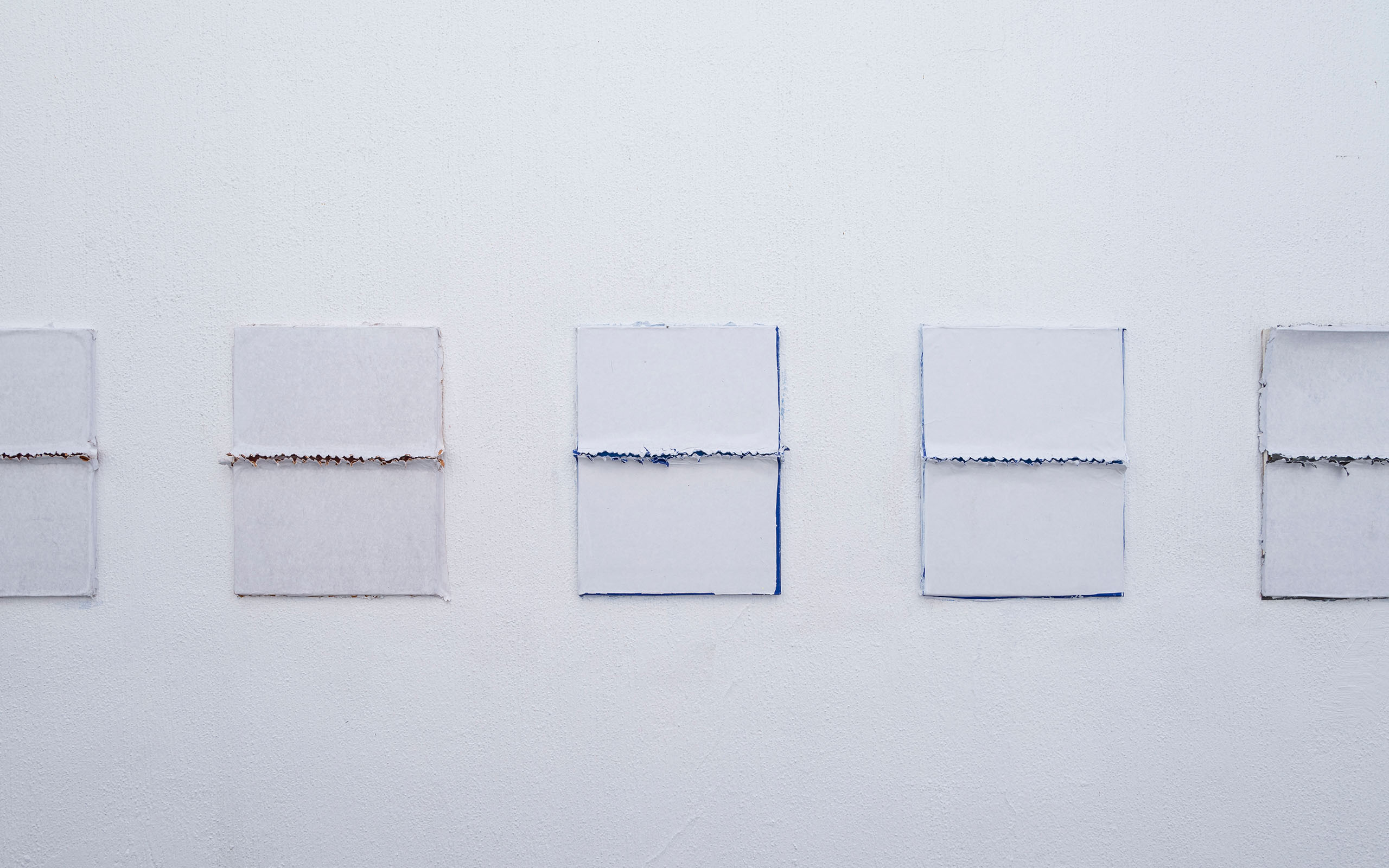

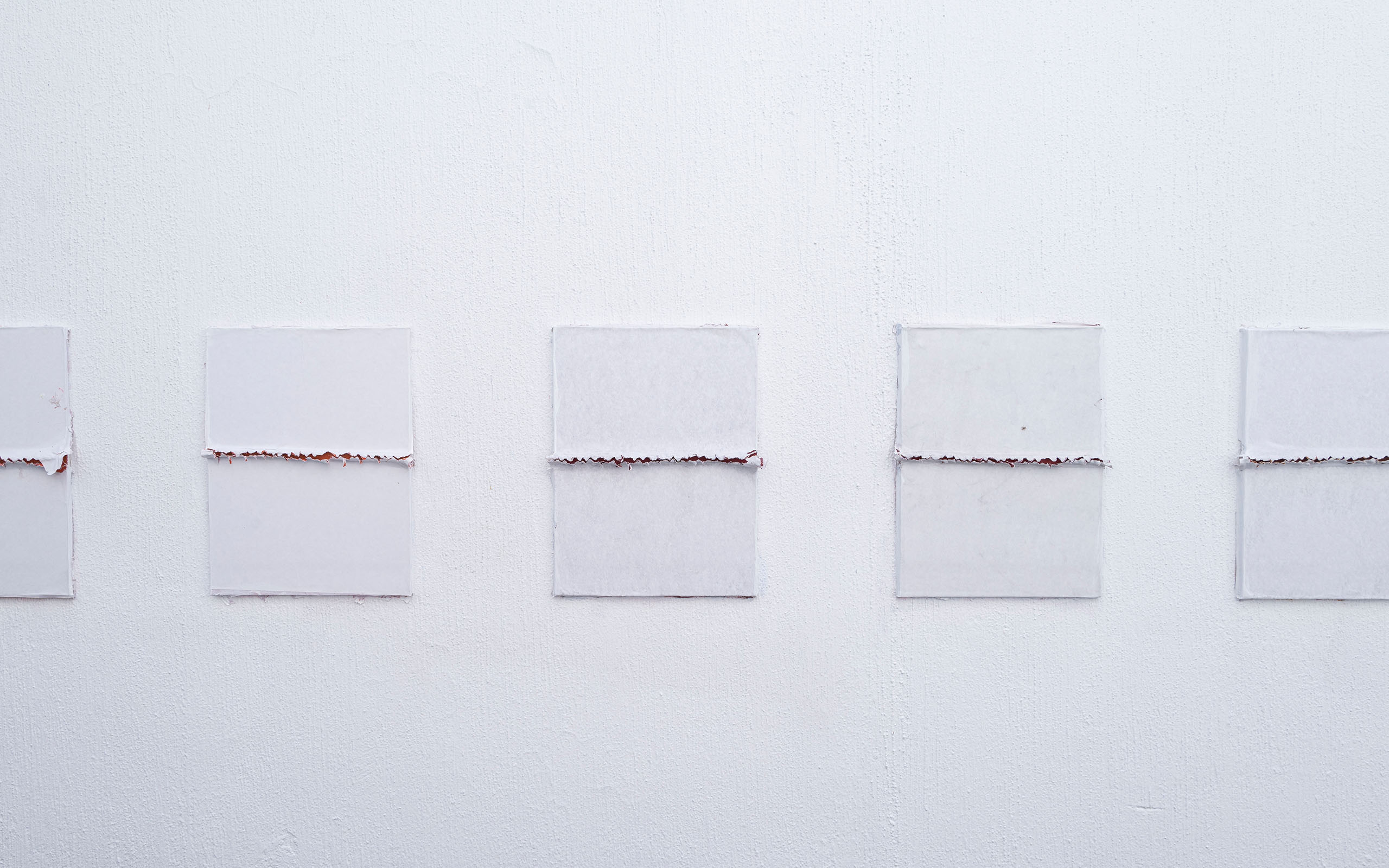

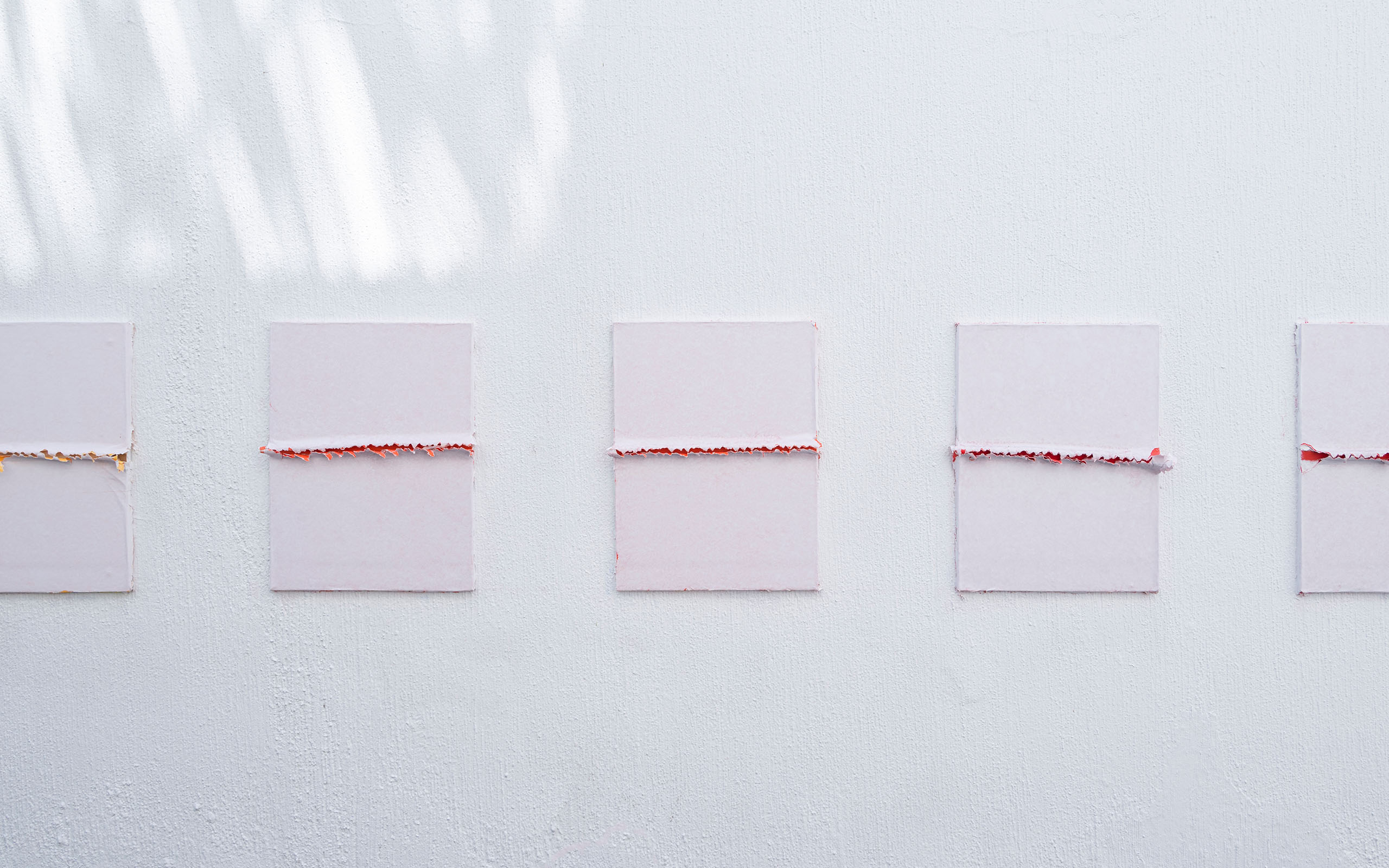

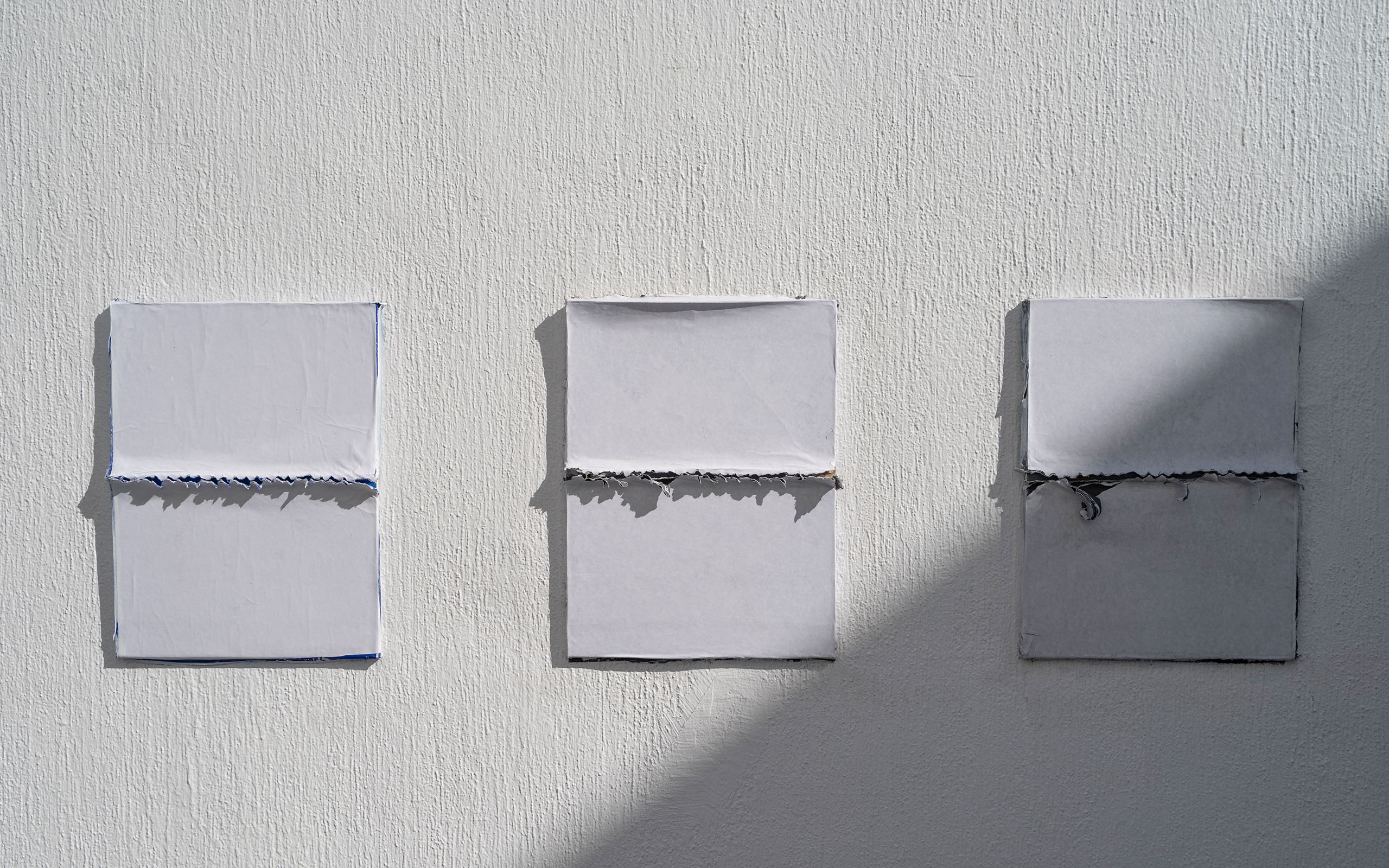

The last piece in the exhibition is Light (2023), a lengthwise wall cut from which light emerges. A fissure with light from who knows where, with no idea of what is on the other side, but that suggests the existence of something else, of a possible issue. One of Bradford’s recurring concerns is the problem of exclusion and of historic injustice with a racial component in the United States, suffered not only by African-Americans but also by Latinos, and especially those of Mexican origin. In this sense, it is significant that Bradford is exhibiting in Guadalajara, the capital of Jalisco, a state with large numbers of emigrants, many of whom head for Los Angeles, where the artist resides and has his studio. The luminous cut in the wall, the light from the other side, suggests a form of coexistence whereby all can live together, from and in the same place, without exclusions. “I don’t believe in access for the few. I believe in contemporary ideas, and I believe in access for more people. How does anybody ever get in? How do new ideas get in?” Bradford was reflecting on art in this instance, but his words have wider implications.

In the end, it is in the cracks, in the fissures, where the possibility of beauty can be glimpsed, where the broken can be restored and promises can be confirmed: “There is a crack, a crack, in everything / That’s how the light gets in.”

Viviana Kuri