Finite Spider’s Web | Arrate Rodríguez

From December 3, 2019 to April 26, 2020

Biombo

Reading room

A text does not exist without a reader to give it meaning: it has no meaning, except through its readers. But how do these di erent readers share the understanding of the same text? What does the receptor gather in, and how? The same texts can be di erently perceived, handled, understood, but a text is not a book: every new reader creates a new text whose meaning will also be modified by the decisions taken in printing it (or reproducing it digitally).

Authors do not write books. Indeed, books are not written at all: they are fabricated by printers, artisans, and other technicians, by printing presses and other

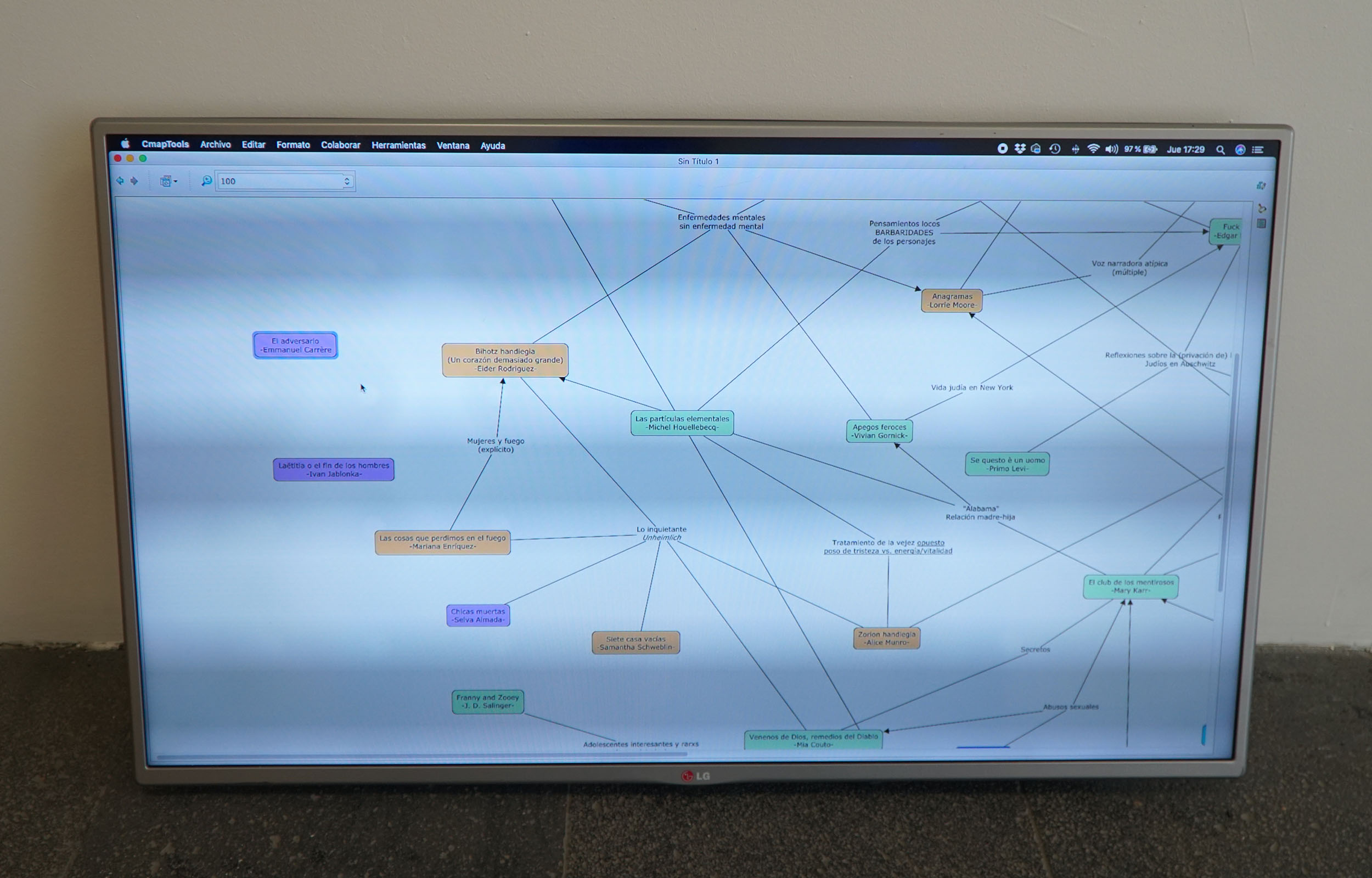

machines. The text does not exist on its own: it cannot exist apart from its material form. “[W]e need to remember that there is no text apart from the physical support that o ers it for reading (or hearing), hence there is no comprehension of any written piece that does not at least in part depend upon the forms in which it reaches its reader. This means that we need to make a distinction between two sets of mechanisms, the ones that are part of the strategies of writing and the author’s intentions, and the ones that result from publishing decisions or the constraints of the print shop. […] Variations in the most purely formal aspects of a text’s presentation can thus modify both its register of reference and its mode of interpretation.” (Chartier: 1994) Of Arrate Rodríguez we could say that she activates yet another device, sharing a series of titles of readings she has done since 2011, when she read Se questo è un uomo (If This Is a Man) by Primo Levi, and thereby drawing a mental map, apparently constructed in real time, of personal associations connected with themes and reflections provoked by

the texts. In this way, she invites visitors to participate as new readers and to makes their own connections along the lines and through the references she establishes. One of the most important elements in Arrate’s work is the idea –the intrinsic necessity– of extending over time the experience of reading, so that it last beyond the pages of the book, like a spider’s web that grows and occupies space in di erent nooks and crannies.

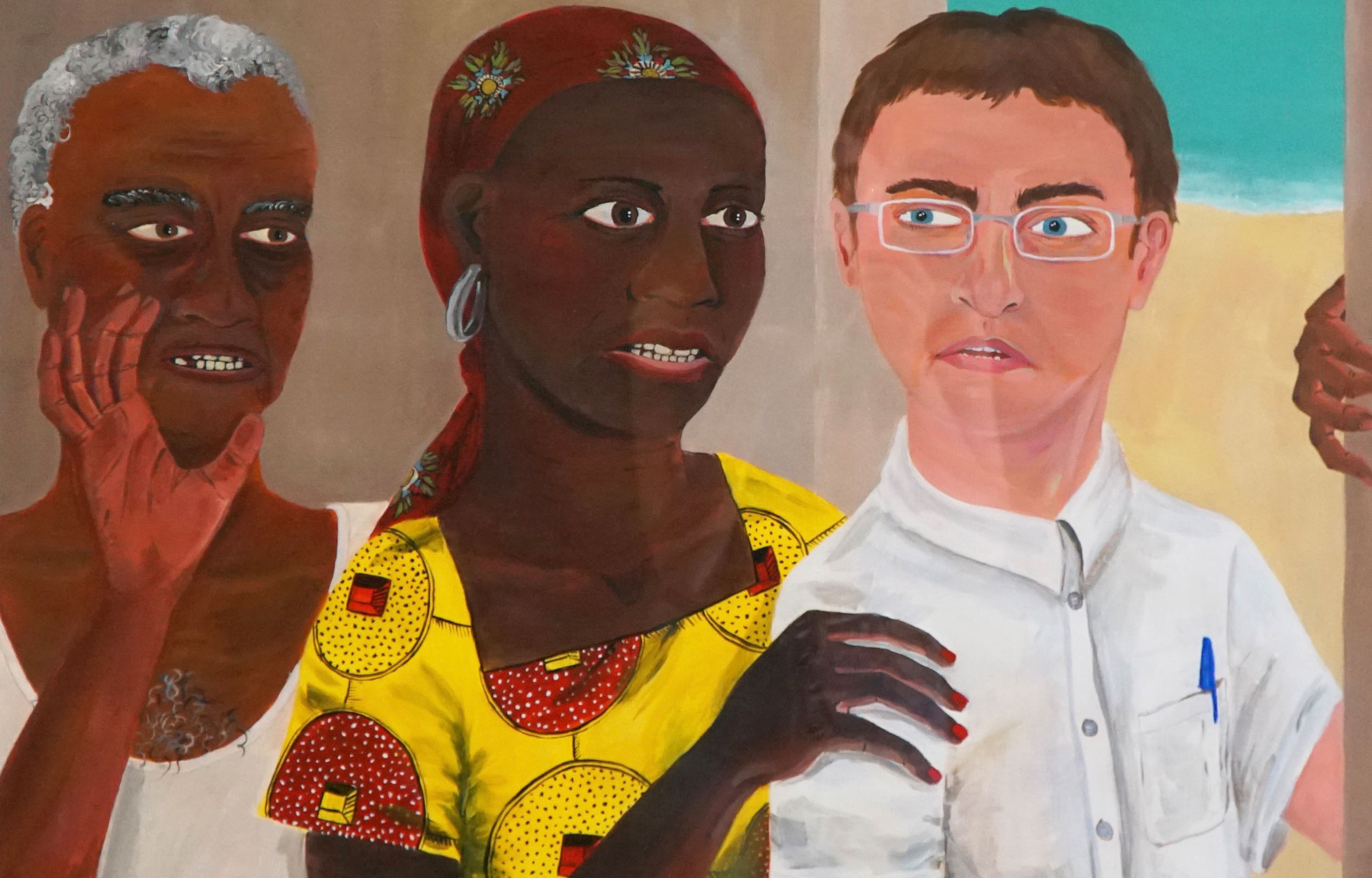

Glimpses of her understanding and interpretation of texts are also made visible in the acrylic paintings based on the experience of the totality of the plots

of five of the books that form part of the map: Las cosas que perdimos en el fuego (Things We Lost in the Fire), by Mariana Enriquez; Freedom, by Jonathan Franzen; Chicas muertas (Dead Girls), by Selva Almeda; Bihotz handiegia (Too Big a Heart), by Eider Rodríguez; and Venenos de Dios, remedios

del Diablo (God’s Poison, Devil’s Relief), by Mia Couto. In this way, she adds a sort of visual epilogue that establishes a unique complicity with the actual

readers of each of the works in question. These exercises are a rare opportunity to glimpse the particular conjectures of another reader, in this case Rodríguez herself. This possibility operates as a sort of journey between minds, but also as a mirror in which each reader or possible reader can express his or her identification or dissent. In any case, the operation is a form of intimate communication between equals who generally read alone and in private. It also recalls, in a certain way, ancient forms of reading, which were performed exclusively aloud. A book does not change, but the way it is read changes. We would like to think that, between private reading, in solitude, and the collective reading of the past, there is a third way that allows for a collective experience and a di erent kind of communication, not necessarily verbal. Finally, on the shelves of the Reading Room during the period of the exhibition, the artist will modify,

on three occasions, the classification of the books, arranging them by the authors’ genders, or by the color of the spines, or backwards (with the fore edges facing out), thereby forcing users to approach the volumes in an unusual way and establishing unaccustomed criteria of reception and selection.

Viviana Kuri