Witness of the Century

Eduardo Abaroa · Doug Aitken · Allora y Calzadilla · Javier Barrios · François Bucher · Agnieszka Casas · Minerva Cuevas · Jose Dávila· Peter Fischli y David Weiss · Sylvie Fleury · Mario García Torres · Thomas Hirschhorn · Yoshua Okón · Gabriel Orozco · Fernando Ortega · Christodoulos Panayiotou · Philippe Parreno · Ana Quiroz · Daniela Rosell · Eduardo Sarabia · Gabriel Sierra · Superflex

From November 28th to April 26th, 2015

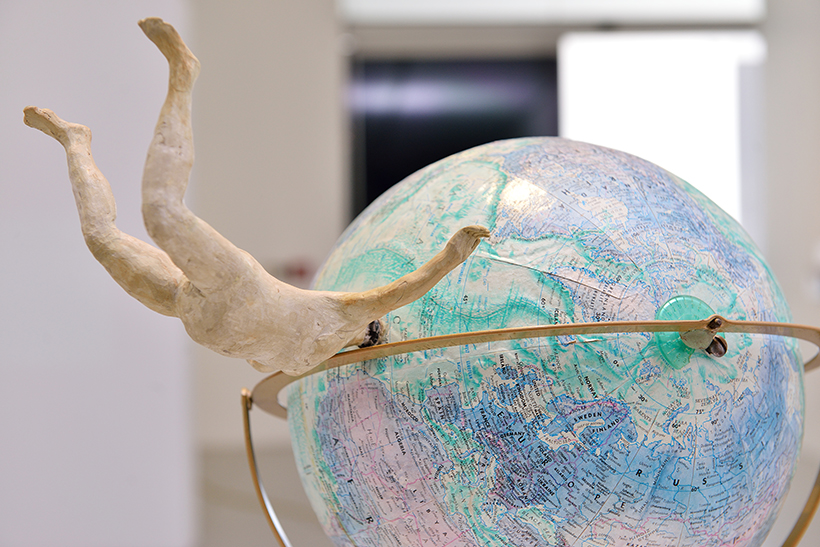

Testigo del siglo proposes a reflection on environmental issues and our ecological emergency through an analysis of contemporary human habits. Accumulation, compulsion, abuse, overconsumption, waste, obsolescence, and the loss of subjectivity in the face of uniformity of thought are some of the issues that Testigo del siglo seeks to address and explore, as symptoms of the human pathologies of our time.

The group of works that make up Testigo del siglo is centered on the interpretation of certain gestures of contemporary society. The exhibition takes its name from Witness of the Century, by artist François Bucher: a caged parrot ends up repeating the words reproduced incessantly by a tape recorder: “Guantánamo, Guantanamera, Guantanamero.” The parrot is the witness that simply repeats what it hears. Unable to offer its own testimony, it symbolizes the animal world subjugated by humanity, but also human beings in thrall within themselves to the dysfunctional lifestyles they have chosen. Who then are those who actually choose? How much free will is permitted to us within a postindustrial capitalist system in which the Global South has little to say and ecological injustice is rife?1

By ecological injustice is meant the extreme vulnerability of the Global South to current and future environmental disasters generated by climate change. Also relevant is the drastically restricted range of consumption options owing to media manipulation, scarcity of information, and lack of economic resources. Nevertheless, Testigo del siglo seeks to affirm the possibility of choice within existing restrictions, in opposition to indifference and apathy, through private dissidence in small actions and decisions that can transform our everyday lives.

In The Three Ecologies, Félix Guattari writes of ecology not simply in terms of the environment, but as a social and mental ecology that must be developed in common by a society united by new objectives, in opposition to fatalistic passivity and soothing discourses. A society made up of individuals of different subjective natures and creative autonomy, struggling against infantile consensus and uniformity of opinion, which cultivates dissidence and the production of unique existences.2

Bucher refers in his work to the Guantánamo detention camp and the reality of the illegal combatant, “whose situation is like that of a Jew in a concentration camp. It is an outside (the camp) that is within the law, but where the law, which claims its own exceptionality, has that person at its mercy, like an animal, not a citizen with rights.”3

The situation for the greater part of the population of the Global South is that of another kind of citizen without rights in the face of decisions about the future of humanity in terms of ecological sustainability. The world powers still refuse to significantly diminish their greenhouse gas emissions, with obvious repercussions for the entire globe. Citizens without basic food rights are at the mercy of corporations that introduce genetic modifications and hydrogenation into their products in order to reduce costs and make them economically viable, denying people’s right to clear information about their origin and at the same time withholding information about possible health risks and consequences.

It was in the 1960s and ’70s that art began to manifest a concernfor the environment. Artists such as Joseph Beuys and Hans Haacke called on spectators to take responsibility for their own choices and the repercussions they may have on society and the environment. Until the 1980s, most projects tended to develop what might be called “restorationist eco-aesthetics”: art that seeks to repair damaged habitats or reactivate degraded ecosystems.4 At the same time, those working in the area of land art not only used nature as a support but also sought to raise environmental awareness, opening the door to various interpretations of art on the basis of ecology.

Various artists and artists’ collectives are currently working on projects that seek to exert a transversal influence, taking into account technological, political, social, and environmental factors. Although Testigo del siglo includes the participation of artists involved in this way, such as Superflex, Allora & Calzadilla, and also Minerva Cuevas, from an activist standpoint, a large part of the work is directed, through the curatorial discourse, at the individual spectator, who in his or her habits or lifestyle is an accomplice to waste, overconsumption, and apathy in the face of the degradation of the habitat and the progressing extinction of its flora and fauna. This includes the common citizen, whose habits daily affect the current and future life of the collectivity. We have also included work that turns its attention to the apparently insignificant, to those moments that are free of this homogeneous and frantic immersion: fixing the gaze on an insect, as Fernando Ortega proposes, or watching a couple riding a bike along a road. And simply listening: no more than that.

Working exclusively with local collections, we have sought to reduce our carbon footprint by limiting transport needs. We are aware that the production of the works depends on industrial technologies, but we believe this very fact buttresses the thesis of the showing: we are all ensnared in global capitalism and our way of life is the cause of the present state of things.

The issue of other resources, such as electricity for the operation of the lighting and air conditioning equipment, remains a problem to be solved. The ideal solution one day would be for the Museo de Arte de Zapopan, as well as other public institutions, to generate its own energy, and to incorporate alternative forms of functioning into its operations.

Viviana Kuri

1 The Global South generally refers to Latin America, Africa, and the greater part of Asia.

2 Félix Guattari, The Three Ecologies (London: Bloomsbury, 2014).

3 Email communication with François Bucher (27 September 2014).

4 T. J. Demos, The Politics of Sustainability: Art and Ecology (2009).

The notion of “ecological disaster” is understood as a catastrophic, uncontrollable, and apparently uncontainable stain caused by human beings on the environment, as an ontological condition of the human species, which appears as a paradox that cannot be overcome. Placed in the twentieth century during which the muscle of capitalism and consumer society strengthened to its fullest. The first decades of the twenty-first century may be understood as an extension of the paradigm of power and consumption of the past century. From this particular narrative strategy our position lays on the theory by Félix Guattari in his book The Three Ecologies, (1989) which attests that ecological imbalance involves not only environmental factors, but equally important are the ecology of social relations and the ecology of human subjectivities.

It is common to encounter “environmentally-friendly” discourses as part of marketing strategies, as if the ecology of the environment was the only cause of the present systemic disaster . This exhibition poses questions related to the other two areas of Guattari’s three ecologies. What kind of relationship do we establish with the objects that surround us? Why is the self-regulation of resources impossible within contemporary social structures?

The works chosen for this exhibition deal with various characteristics of contemporary society: unemployment, marginalization, racism, loneliness, boredom, anxiety, and neurosis. They reflect the tensions interwoven in this complex tangle of features and speak to the hubris with which our society overpowers, the irrationality of the accumulation, the sacralization of profit, and the corporatist policies with commercial ends, by which the dynamics of our society are circumscribed, a symbolic universe that reduces every subject to the role of consumer and confines every object to the category of merchandise.

Three pieces constitute the spinal column of the exhibition: “Critical Laboratory” has been conceived by Thomas Hirschhorn as a space both mental and physical, secret, peripheral, in which the question may be posed: How can I achieve a critical position? Through images taken from the world of fashion, luxury products, economics, philosophy, culture, war, suburbia, and history, this space could well be a laboratory for biological weapons, pharmaceutical products, or synthetic drugs. The spectators are directly addressed: the texts on the Stockholm syndrome, the plastic chairs and flowers, the tape and lights seek to provoke a “crisis” in their viewpoints and opinions.

In “Witness of the Century,” the piece that gives its name to the exhibition as a whole, François Bucher creates a domestic habitat for a parrot that interacts with a sound teaching it to say three words: “Guantánamo, Guantanamera, Guantanamero.” The reference to Cuban independence is overridden by the type of cognitive exchange in play: a caged animal figure being trained to speak a language it does not understand.

Finally, Doug Aitken’s video piece “Migration” is a juxtaposition of a postindustrial landscape (a decadent incarnation of suburban and rural areas in industrialized countries) and wild animals interacting with an unknown medium. In an affected cinematic style, a camera captures a bleak succession of interactions with objects and situations in which the witness, behind the camera, remains suspended in a moment of intimacy.

As part of the criteria that governs this project was to draw on works chosen exclusively from local collections, in order to activate a different ecology: that of collecting itself. There are some important private collections in Guadalajara, which circulate poorly in local institutions. This decision was in line with our own curatorial discourse and our intention to shake up the cycle of production, consumption, storage, and exhibition of works fostered by globalization in the contemporary art market. Likewise, the project seeks to reduce its carbon footprint through diminished air transport, in keeping with the proposals of the Reduce Art Flights campaign, initiated in 2007 by the British artist Gustav Metzger.1

A robust program of parallel activities specially prepared to encourage participation, awareness, and dialogue with the community, creates a network of interconnections that, from different platforms, generates resonances and helps to strengthen the social tissue. The speed with which the coming ecological disaster is approaching demonstrates that individual efforts are no longer enough. A solution can only be arrived at collectively, through a change to an ethical paradigm that will save us from extinction.

Humberto Moro